Popular:

Popular:

Motivated by the Industrial Revolution’s impact on women, who were now joining the workforce for less pay than men, and frustrated by their lack of civil, political, social and religious rights in society, activists, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, organize America’s first women’s rights convention. The historic two-day Seneca Falls Convention brings 300 attendees to New York to discuss the role of women in society and kickstart a national movement to bring about equality for women. The Declaration of Sentiments is signed, outlining grievances and bravely calling for equal treatment under the law, specifically women’s right to vote.

The controversial Seneca Falls Convention and its provocative Declaration of Sentiments are unwelcome, as conventional gender roles have always been the norm, as has the belief that society functions best when men and women operate in separate spheres: men in public life and women in the home, where they have complete freedom. As such, there’s no need to address women’s suffrage, especially if it comes at the expense of the family institution or public support for other rights, like property rights for married women.

The suffragist movement splits over disagreement about the 15th Amendment, which grants African American men the right to vote. A resentful Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton insist on pushing federal lawmakers to include women in the amendment and form the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) to address wide-ranging equality. Meanwhile, the less radical American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) focuses solely women’s suffrage, in a state-by-state campaign.

While the post-Civil War nation is embroiled in sensitive race issues, especially African-American male suffrage, divided lawmakers in the North and South feel women’s suffrage may endanger more pressing national political advancements. Since America’s founding, husbands have always represented their wives in societal matters outside the home and have voted for them. Just because voting rights for black men are changing doesn’t mean that women’s roles have changed.

With more than 6,000 adult males and only 1,000 females in the western territory of Wyoming in 1869, legislators make the strategic decision to sign a law allowing women to vote as an attempt to attract single, marriageable women to come and settle in the rugged and remote territory. The suffrage movement overlooks the motivation since the outcome is for the greater good; this sets the path for Colorado (1893), Utah (1896), and Idaho (1896) to become women’s suffrage states.

Most men in Western mining towns and camps dismiss women’s political capacities to vote. Saloon owners, brewers and pioneers especially fear that women voters may be more likely to crack down on liquor if they have the chance to vote, given their increasing involvement in the temperance movement at the time. However, women voters may possibly tip the balance in favor of native-born (white) voters compared to the growing presence of blacks and immigrant workers.

Faced with public apathy and political indifference and living under a government in which they have no say, the divided women activists of both the NWSA and the AWSA realize they need to set their personality and strategy differences aside and focus solely on the right to vote as the means to give women a fuller voice in national affairs. Consequently, the splintered NWSA and AWSA merge to form a mainstream National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and begin state-by-state campaigns to obtain voting rights for women.

Many women in the elite circles of society begrudge the women’s suffrage movement for trying to disrupt the status quo, as they are enjoying the existing social order and don’t appreciate having traditional gender norms challenged. Besides, as women are already busy with domestic responsibilities, society disapproves of those who are asking the federal government to impose additional burdens onto women, namely staying informed of political issues and voting.

After 10 hours of debate in front of galleries packed with loyal suffragists, the U.S. House of Representatives does a major disservice to its constituents and country by voting to reject (204 to 174) a constitutional amendment that would have given women the right to vote. While this is the second defeat for the suffrage amendment in less than a year, suffragists remain optimistic since the issue is actually – finally – being discussed in Congress after a 47-year gap in addressing this issue.

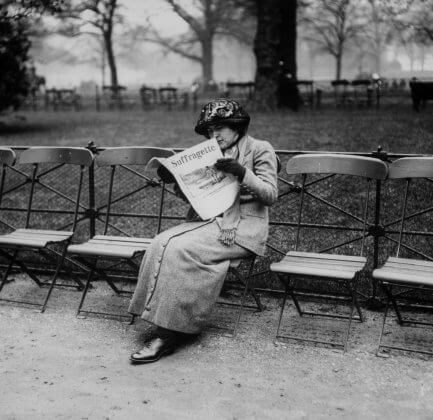

While members of government voting against women’s suffrage are not against women per se, they are opposed to corrupting women by granting them the right to vote, which would force them into the sphere of politics where their modesty and delicate sensitivities will surely be offended. Given that very few women are ever observed reading newspapers in public, it is evident that they are generally disinterested in politics, which would make them unworthy and uninformed voters.

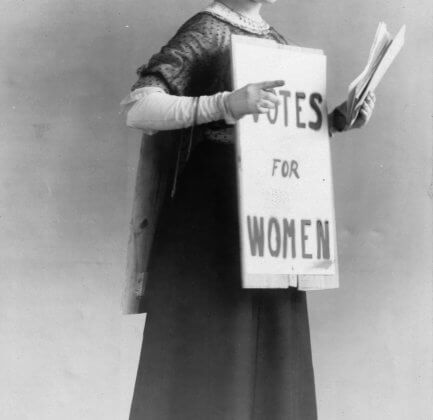

Frustrated by a lack of progress, feminist activist Alice Paul and colleagues form the National Woman’s Party and start introducing methods used by the suffrage movement in Britain. They engage in nonviolent demonstrations, parades, and picketing the White House in response to President Woodrow Wilson’s and other Democrats’ callous dismissal of the Suffrage Amendment. In July 1917, picketers, including Alice Paul, are unjustifiably arrested on charges of “obstructing traffic.”

These uncouth and indecent women who are making fools out of themselves by demanding to be treated like men are not appreciated. Their abhorrent marches and songs are a distraction in Washington DC, especially while America is at war. These militant women’s actions deserve the violent reactions they are provoking from bystanders. They are bringing shame to their husbands and children.

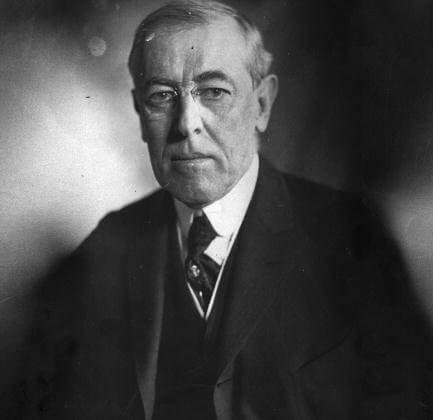

Following women’s contributions during World War I, President Woodrow Wilson, previously indifferent to women’s suffrage, finally shows his appreciation for America’s women by publicly supporting their right to vote. In a much appreciated speech before Congress, Wilson asks Senate and House members: “We have made partners of the women in this war… Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”

Just because a historically anti-feminist Woodrow Wilson changes his mind about women’s suffrage doesn’t mean that the rest of the country is ready to. Opponents to women’s suffrage range from the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage to the liquor and manufacturing industries, each fearing that women would support prohibition and reform legislation that would boost labor costs. Some southerners also don’t want to further expand voter eligibility, and the Catholic Church clergy still believes that each sex has its own God-given sphere of activity.

After a hard-fought and respectable personal effort by President Wilson, inspired by the unbreakable spirit of the suffragettes to courageously fight for due equality, the Nineteenth Amendment becomes part of the U.S. Constitution. It states, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Resigned to the end of the anti-suffrage movement with the disappointing passing of the Nineteenth Amendment, most women who previously opposed suffrage now willingly embrace their civic duty and exercise their right to vote. Many opponents turn their energies into organizing political anti-feminism movements.