Popular:

Popular:

Plantation owners in Hawaii and California turn toward Japan after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 forbids them from continuing to hire Chinese laborers in their sugar cane, coffee and pineapple fields. Japanese citizens are lured to come work with the promise of earning exponentially more than they could in their home country.

After the new Meiji emperor of Japan starts allowing citizens to emigrate, tens of thousands of Japanese journey to Hawaii in search of a better life. However, after a while, they seek better working conditions, higher wages and, especially, more educational opportunities in California, Oregon and Washington State, taking agricultural jobs and settling into American life.

A significant immigrant surge between 1880-1920 transforms American culture and society, spurring antagonism among native-born Americans who fear losing their cities to undesirable newcomers, especially immigrants from countries other than northern Europe. To protect American livelihoods from the economic threat that Japanese immigrants, specifically, pose by filling agricultural jobs, Congresses passes the Immigration Act of 1924, halting the influx of Japanese and other east Asian immigrants until 1952.

It’s highly unfair and inaccurate that Japanese immigrants are being blamed for taking away unskilled, low-paying jobs since they are leaving agricultural work and beginning to own land and lease it to others. Despite, having to withstand widespread prejudice against them, including school segregation and not being allowed to become naturalized citizens, Japanese nationals (“Issei” in Japanese) are nonetheless prospering and integrating into American society, making a life for themselves and their American-born children (“Neisi” in Japanese).

Americans’ nerves are high following Japan’s vicious surprise attack on the Pearl Harbor military base in Hawaii. They fear further devastation and question whether it will come from outside or within the country. After President Roosevelt declares war on Japan, martial law is also declared in Hawaii for national security. The FBI understandably begins detaining Japanese nationals and their American-born children on both U.S. coasts. In New York, Japanese nationals are transported to Ellis Island and held in custody indefinitely, given the necessity to question their ties with Japan.

Despite the U.S. Intelligence “Munson Report,” commissioned by President Roosevelt one month prior to Pearl Harbor, which concludes that the majority of Japanese living in America were loyal to the U.S. and didn’t pose a threat to national security even in the event of war, innocent Japanese residents are unjustly rounded up after Pearl Harbor. Japanese nationals are victims of rising paranoia and bigotry targeted at them, both adults and children. The FBI needlessly searches thousands of Japanese American homes, unduly confiscating short-wave radios, cameras, heirloom swords, among other items.

In a state of war, America and all of its citizens need to remain vigilant and weary of domestic spies, traitors and alien enemies. In an effort to do so, President Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, authorizing the military to relocate or intern any civilian who might threaten the U.S. war effort – without the need of a trial or hearing. While the order does not specify Japanese Americans, they are understandably the only group to be imprisoned in detention camps as a result of it.

Though they were just as shocked and traumatized by Pearl Harbor as everyone around them, tens of thousands of Japanese legal residents are systematically rounded up and incarcerated in cramped, unsanitary quarters in detention centers, thanks to President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Even for U.S.-born Neisi, the Bill of Rights no longer applies. Treated as less than human, evacuees can only take as many possessions as they can carry.

As America is at war on several fronts, yet has to keep its citizens at home safe on dwindling resources, the government needs to enact broad policies. President Roosevelt therefore signs Executive Order 9102, establishing the War Relocation Authority, which oversees the relocation of the 100,000 Japanese-Americans under suspicion from the western halves of Washington State, California, Oregon and parts of Arizona for national security. For added security, a curfew is imposed in these areas–all those of Japanese ancestry must remain at home from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. The Wartime Civil Control Administration opens 17 temporary “Assembly Centers” until the 10 permanent camps in California, Arizona, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas and ready for their transfer in May.

After the Army issues the first Civilian Exclusion Order for Bainbridge Island near Seattle, Washington, the journey of shame begins for those U.S. citizens and legal permanent resident aliens who happen to be of Japanese ancestry. The first 45 families are given one week to prepare to fit their entire lives into just a few articles that can be carried. Their homes, belongings, pets and livelihoods are all left behind. Forced to abandon everything they’ve worked for, some even forcibly separated from their families, the innocent victims of wartime hysteria begin a new life. Barbed wire, armed guards, cramped barracks, unsanitary conditions, disease and boredom are now their new reality. In the camps, they begin a life totally devoid of freedom, identity and dignity.

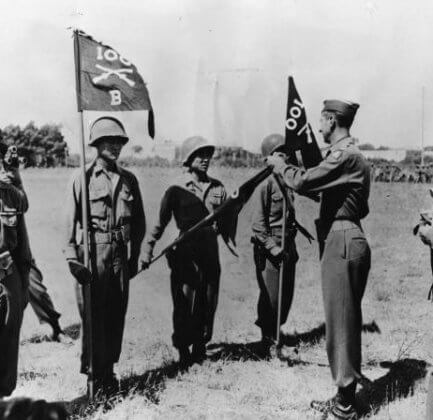

To win a just war, America needs Japanese-Americans for their valued translating skills to spy on Japan. The War Department forms a segregated unit of Japanese-American soldiers, 442nd Regimental Combat Team. They call for volunteers from Hawaii, where Japanese-Americans were not incarcerated, and from the internment camps. By March, there are 10,000 Japanese-American volunteers from Hawaii and another 1,200 from the camps. However, a year later, the War Department is forced to impose a draft. Those who refuse to serve face fines and prison time.

Understandably, being drafted into the U.S. army while they and their families are held in detention camps, does not appeal to most Japanese-Americans. Naturally, many protest, demanding the government recognize their civil rights and that they aren’t segregated. Not surprisingly, the quota for Japanese-American volunteers falls short, and the government unfairly imposes a draft on them. While the majority comply, a few hundred understandably resist the draft, and are brought up on federal charges. Once in the army, they face soldiers who eye them with suspicion and bigotry. Nonetheless, they fight heroically.

The Supreme Court rules that loyal citizens cannot be lawfully detained. The Roosevelt administration declares that Japanese-Americans are now legally cleared to leave the concentration camps, thus starting a six-month process of releasing internees, either to resettlement facilities or temporary housing while they figure out how to return to the West Coast.

While the Japanese-Americans welcome the good news of finally being free, they are worried about where and how to start their lives over again outside of the camps, especially as they lost their jobs, properties and savings. Also of grave concern are the anti-Japanese groups whose prejudice against them has picked up steam during their four years of incarceration. Their internment may have ended, but anti-Japanese sentiment is still prevalent along the West Coast. Therefore, some remain in the camps despite that all are freed.

Following Nazi Germany’s surrender in May, the U.S. manages to bring the war to an end though a necessary but devastating act of dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, forcing Japan to surrender on Aug 14. The end of World War II signifies that the external Japanese threat is over. The victorious U.S. can breathe a collective sigh of relief and concentrate on healing its domestic divisions. The government starts by announcing that it will begin closing the Japanese-American relocation centers.

Despite the war’s end, some 44,000 Japanese-Americans remain in the internment camps until the summer of 1946, when all 10 camps are finally closed. Most detainees have almost no personal belongings to take home with them, having sold most of them before they entered the camps. While many have no homes or jobs to return to, others succeed in returning to the West Coast and reclaiming what was rightfully theirs.

In an effort to recognize the injustice that befell Japanese-Americans who were removed from their homes in Pacific Coast for the sake of national security during World War II, and to try to make up for what they lost, Congress passes and President Truman signs the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act. It authorizes compensation of approximately $38 million to settle 23,000 claims for damages totaling $131 million. It’s a start.

While the U.S. government is finally admitting to its role in robbing Japanese-Americans of their civil liberties, the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act is not enough. The $38 million price compensation is only a small fraction of the estimated loss in income and property they caused the victims. While it is the first civil rights-associated law enacted in the 20th century, the Act is ineffective as it requires victims to jump through hoops trying to prove their losses, creating even more undue stress.

Having the integrity to confront its past actions, the U.S. government establishes the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, which investigates the detention program and the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066. The Commission holds hearings in 10 places, and hears testimony from over 750 witnesses. Committed to reconciliation, the Commission’s findings, published in a 1983 report, acknowledge that racial prejudice, war hysteria and widespread ignorance of Japanese-Americans drove the Presidential order, which was not justified by military necessity.

Finally, the U.S. government is not only taking responsibility for its actions toward Japanese-Americans during WWII, but also recognizing the racist motivations behind them. The Commission – and its conclusions – are a crucial, overdue gesture, which will go a long way to nurture healing and forgiveness among Japanese-Americans toward the government. The Commission’s recommendation that Congress apologize and make a tax-free payment of $20,000 to each surviving evacuee who suffered being removed from their places of residence is bittersweet yet appreciated.

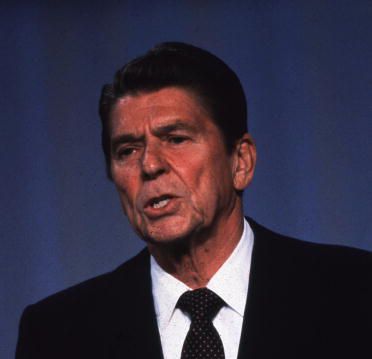

President Ronald Reagan signs HR 442, otherwise known as the Civil Rights Act of 1988, into law. Based on the Commission’s important conclusions for America to take responsibility for its past unjust actions, this Act acknowledges the personal hardship caused by the Japanese-American internment program, which incarcerated more than 110,000 individuals of Japanese descent, was unjust. As such, President Reagan offers an apology and follows up on the recommended reparation payments of $20,000 to each person incarcerated.

President Reagan’s public apology and the $20,000 in reparations are a most welcome symbol of reconciliation between the U.S. government and Japanese-American citizens and legal residential aliens. It has been a long time coming, but this redress for the wrongs and humiliation that Japanese-Americans suffered at the hands of their government, stated publicly by the U.S. president, is valued, especially as the report has been into legislative language. This helps ensure that such injustice will not happen to Americans again.